Could Lithium Be a Missing Piece in Alzheimer’s Disease? A New Research Perspective

I’ve briefly touched on Lithium before - but it’s in the news again. A fascinating new study from Harvard Medical School is garnering attention across the neuroscience world for proposing something that might feel both surprising and logical, that lithium deficiency in the brain could be a driving factor in Alzheimer’s disease, and that restoring lithium levels might help prevent or even reverse aspects of the disease.

What Did the Study Find?

Published in Nature after more than a decade of work, this study shows that:

Lithium is naturally present in the brain. Until now, most research treated lithium mainly as a pharmaceutical used in psychiatric conditions like bipolar disorder. But this team demonstrated that lithium exists at biologically meaningful levels in healthy brains.

Lithium levels drop early in Alzheimer’s. In both human brain tissue and animal models, lithium depletion was one of the first detectable changes associated with cognitive impairment.

Plaques may sequester lithium. Amyloid-beta, the early hallmark protein aggregates in Alzheimer’s, binds lithium - reducing its availability in the brain.

In mice, lithium deficiency accelerated pathology. Lower lithium levels triggered inflammation, synaptic loss, myelin degradation, and memory decline, all classic Alzheimer’s features.

A lithium compound reversed disease markers in mice. Using a compound called lithium orotate that avoids being sequestered by amyloid, researchers were able to restore memory and reduce pathology in mice - at doses far lower than those used in bipolar treatment.

This last point is especially important because lithium in high doses (such as lithium carbonate used in psychiatric settings) can be toxic, especially in older adults. The notion here is micro- or physiological dosing of lithium, not high, mood-stabilizing levels.

Why Lithium Might Work: The GSK-3 Connection

One reason lithium keeps resurfacing in Alzheimer’s research - despite decades of neglect - is its relationship to a powerful regulatory enzyme called GSK-3 (glycogen synthase kinase-3).

What is GSK-3?

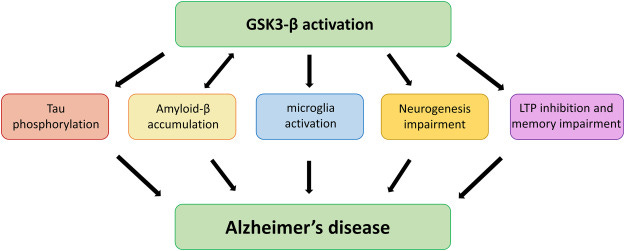

GSK-3 is a master regulatory kinase - an enzyme that controls the activity of many other proteins by phosphorylating them. In a healthy brain, GSK-3 activity is tightly restrained. In Alzheimer’s disease, it becomes chronically overactive.

That matters because GSK-3 sits at the crossroads of several core Alzheimer’s processes:

Tau pathology:

GSK-3 is one of the primary enzymes that hyperphosphorylates tau. Excessive GSK-3 activity destabilizes microtubules, promotes neurofibrillary tangles, and closely tracks cognitive decline.Amyloid biology:

GSK-3 promotes amyloid-β production and is itself activated by amyloid, creating a self-reinforcing feedback loop that accelerates pathology once it begins.Neuroinflammation:

Overactive GSK-3 drives pro-inflammatory signaling (via NF-κB and cytokines), keeping microglia in a chronically activated, neurotoxic state.Insulin resistance in the brain:

Insulin signaling normally suppresses GSK-3. In Alzheimer’s - and particularly in APOE4 brains - impaired insulin signaling removes this brake, allowing GSK-3 to remain switched “on.”Mitochondrial dysfunction and synaptic loss:

GSK-3 overactivity disrupts energy production, impairs synaptic plasticity, and promotes neuronal apoptosis.

In short, GSK-3 doesn’t cause one Alzheimer’s feature - it coordinates many of them.

Where lithium fits in

Lithium is one of the most potent known inhibitors of GSK-3.

At low, non-psychiatric doses, lithium:

Directly inhibits GSK-3 activity

Indirectly suppresses GSK-3 by improving insulin signaling

Reduces tau hyperphosphorylation

Dampens neuroinflammatory signaling

Supports autophagy and mitochondrial function

This is a fundamentally different mechanism than targeting amyloid plaques or tau tangles after the fact. Lithium acts upstream, at a control node that influences both.

Importantly, this does not require the high serum lithium levels used in bipolar disorder, levels that carry real toxicity risks. The emerging Alzheimer’s literature increasingly points toward micro-dosing, where GSK-3 is gently down-regulated rather than shut down.

Why this connection is often missing from the literature

Most Alzheimer’s papers focus on isolated pathways such as tau, amyloid, inflammation, metabolism, rather than the enzymes that integrate them. GSK-3 often appears in the background of these studies, but rarely as the central unifying factor.

When viewed through a systems-biology lens, however, the logic becomes difficult to ignore:

If Alzheimer’s represents a state of chronic GSK-3 overactivation, then lithium’s long-observed neuroprotective effects suddenly make sense.

This doesn’t make lithium a cure, but it does make it a rational intervention worth serious attention.

Bottom line

Lithium’s relevance to Alzheimer’s is not mysterious or anecdotal. It stems from its ability to modulate GSK-3, a central enzyme linking tau pathology, amyloid biology, inflammation, insulin resistance, and neuronal survival. Seen this way, lithium is not an outlier, it is one of the few interventions that acts where many Alzheimer’s pathways converge.

Why Is This Important?

For decades, Alzheimer’s research has focused heavily on amyloid plaques and tau tangles, with limited success in changing clinical outcomes. This study proposes a fundamentally different angle:

Instead of focusing solely on downstream pathology, look upstream to an essential trace element whose deficiency may open the door to neurodegenerative cascades.

Some prior population studies had hinted that areas with higher natural lithium in drinking water had lower dementia rates, and long-term lithium therapy in psychiatric patients has been associated with lower Alzheimer’s incidence.

Mechanisms by Which Lithium Might Help

Lithium has been studied for its neuroprotective properties for years. Preclinical and clinical research has shown that it may:

Inhibit GSK-3, an enzyme involved in both amyloid and tau pathology.

Reduce neuroinflammation and oxidative stress.

Improve cell survival, mitochondrial function, and autophagy - all processes implicated in Alzheimer’s.

Correlate with slower cognitive decline in some human studies.

The new Harvard work extends these concepts by suggesting that the brain actually needs a baseline lithium level for normal function - much like essential vitamins or minerals - and that depletion is not just an association but a contributor to disease progression.

Important Caveats

This research is still in early stages:

Most of the dramatic effects were observed in mouse models, which don’t always translate directly to humans.

Clinical trials in humans for Alzheimer’s prevention or therapy using lithium have been limited and mixed, and no lithium compound is currently approved for Alzheimer’s treatment.

The form of lithium used in the mice (e.g., lithium orotate or other amyloid-evading compounds) has not yet been tested in robust, controlled human trials.

Where this field might head next:

The implications of this research extend beyond a single study:

Biomarker development: Measuring lithium levels in blood or cerebrospinal fluid might help identify individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s earlier.

New therapeutic strategies: Designing lithium compounds that avoid sequestration and toxicity could lead to treatments that modify the disease process rather than just its symptoms.

Nutritional neuroscience reconsidered: If lithium is truly acting like an essential nutrient for brain health, baseline requirements and dietary/lifestyle factors may gain newfound importance.

Bottom Line

Emerging research is reframing lithium from a psychiatric drug to a potential missing piece in our understanding of Alzheimer’s disease. While it’s too early to declare it a cure or a clinically validated therapy, the idea that lithium deficiency might help explain and potentially treat or prevent Alzheimer’s is a bold and testable hypothesis that has ignited scientific interest.

For this APOE4/4 carrier, and already beyond the average age of Alzheimer’s onset for many with my genotype - waiting passively for research to “catch up” is not an option. I’ve spent years studying the lithium literature and am comfortable with the risk–benefit profile at very low doses. Based on that work, I take 5–10 mg of lithium orotate nightly, a practice I began a few years ago after reading a 2015 study suggesting lithium’s potential to support cognition. For me, this is not experimentation, it’s an informed, measured decision grounded in science, context, and personal risk tolerance.

Other references:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19754466/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29232923/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=lithium+alzheimer%27s

https://www.science.org/content/article/could-lithium-stave-alzheimer-s-disease?

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304394021004225?via%3Dihub

I am APOE4/4 and blessed with LP(a). I buried my parents, brother, two aunts, three grandparents who died from dementia/Alzheimers. More remote relatives have also passed from the disease. I started have mild memory issues recently. I read Nick’s Substack and others on YouTube on lithium. I started 3mg of lithium ororate and few months ago and saw immediate benefits including better recall of numbers, passwords, clarity of vision, recall of read material and calmer emotions. Just increased to 5mg as an experiment with only minor improvement. I will drop back to 3mm next month unless I see more benefit. No side effects noticed. I worry about weight gain as I am trying to lose my recent 15lb gain and I seem to have stalled.

Thank you Karin. I share the same sentiment expressed by James. I too have been taking Lithium orotate for the past 2 years after reading the data and following you as well as Nick’s Substack. The past year I increased the dose to 10 mgs.